Ultra processed foods are in the news more and more. A recent meta-study found there are a myriad of health issues linked to diets comprised primarily of such foods. When thinking about the level of processing, foods are typically categorised into 4 groups: unprocessed or minimally processed, processed culinary ingredients, processed foods and ultra-processed foods.

Processing is not a bad thing in and of itself. Pickling, fermenting, canning, even chopping and cooking are processes. We process things to turn them into food at home, in restaurants and in factories. Ultra-processed foods are distinctive in that they change the nature of the original ingredients, such that very little of the original whole food is left, and they include chemicals that you would not find in an ordinary kitchen. These include emulsifiers, artificial colours and flavours, stabilisers, sweeteners, and other additives to make them taste better and last longer. They also are fatty, salty or sugary and lack dietary fibre. What we might think of as empty calories.

Ultra-processed foods are also less expensive and, because they last longer than fresh foods, are less risky for a tight household budget. But we pay for this low cost in other ways. Individually, we pay for this food with our health. We also pay collectively, if somewhat unevenly, for it with the environment. Ultra-processed foods drive mono-crop production that undermines ecosystems and harms biodiversity. The processing is also energy-intensive and dependent upon petrochemical inputs, thereby contributing to climate change.

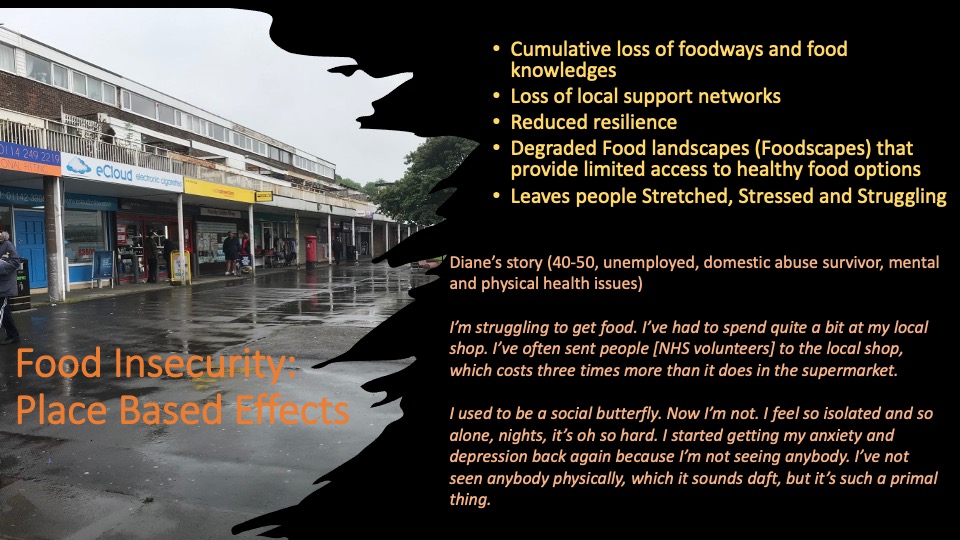

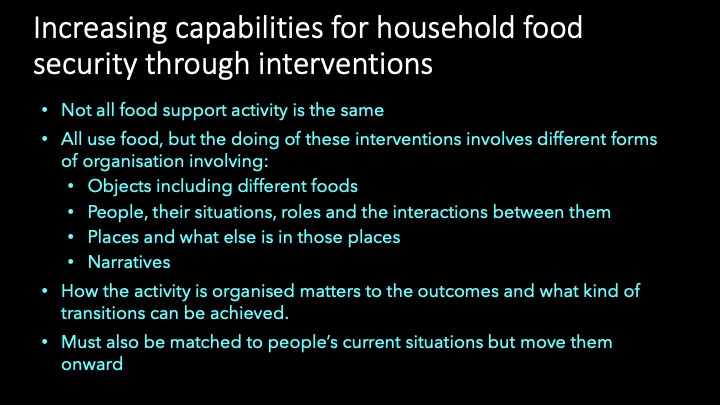

We can tell people to stop eating these foods, but educational campaigns won’t work on their own. People need to have the capability to eat differently. If those foods that are better for you are not available in the place where you live or they are too expensive then all that the education will do is create further feelings of guilt.

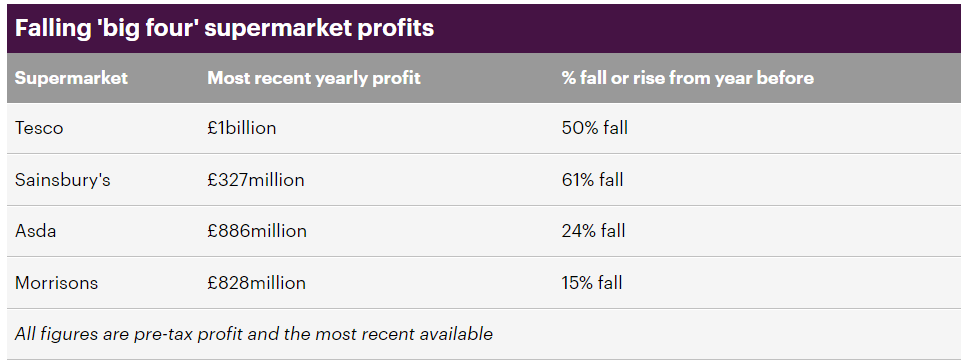

Ultra-processed foods are a key part of a system that rewards producers for creating these foods in the form of profits now, whilst undermining our global food security now and into the future. Because this is a systemic problem we need systems solutions that intersect at all points of the supply chain and operate at different scales. Introducing disincentives for the production and sale of ultra-processed foods, shifting to agroecologiecal farming practices, and re-introducing these better foods into neighbourhoods all need to be considered.

I recently participated in a webinar by Healthy Diets Healthy Life (HDHL) as part of the European Commission’s Bioeconomy Changemakers festival. In addition to learning about HDHL and hearing two other speakers talk about ultra-processed foods from a bio-economy and a nutrition perspective, I talk about the contexts within which people access and purchase food. My section starts at about 38 minutes in.

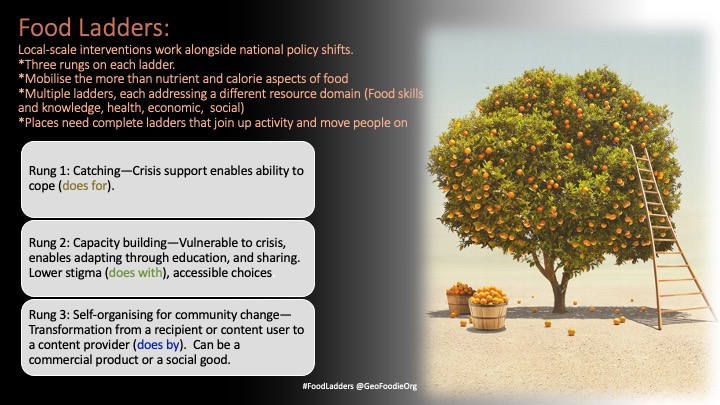

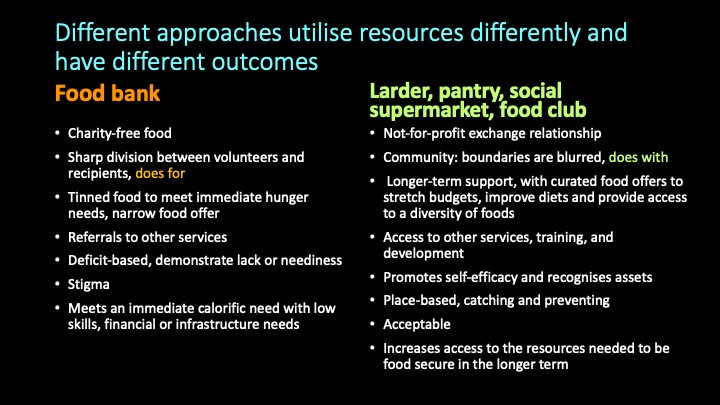

So what can we do right now? We can pressure government to put constraints on the way those in the food sector operate and provide incentives to act in a way that is better for both health and the environment. Individually, we can also try where we can to introduce more foods into our diets that replace the ultra-processed foods we currently eat. As a society, including commercial organisations, we can also support initiatives that help people by expanding their access to and knowledge of those foods that are better for them, which do so in non-stigmatising ways. I talk about two such initiatives in the video.

You must be logged in to post a comment.