This entry focuses on two approaches to understanding poverty and its links to how people may be food secure. The first approach, the economic model, is described, and its implications are considered. The second, the capabilities approach, is similarly explained and elaborated. The entry also argues that the links between poverty and food security are as salient for wealthy countries as for less affluent countries. The entry concludes by discussing future research and practice informed by the capabilities framing.

This blog post is a slightly extended version of an entry in the forthcoming Elgar Encyclopedia of Food and Society.

Keywords: Food Security, Poverty, Food Poverty, Capabilities, Place, Food Ladders

Dr. Megan Blake, ORCID: 0000-0002-8487-8202

INTRODUCTION: POVERTY AND FOOD

Ending hunger, food insecurity, and all forms of malnutrition is a sustainable development goal to be achieved by 2030. Approximately 38% (3.1 billion people) of the world’s population is estimated to struggle to get the food they need to live a healthy life (FAO et al. 2022). Food insecurity is defined as the ability, now and in the future, to access, afford and utilise food of a sufficient quantity that is safe, healthy and culturally appropriate. It is widely recognised that poverty strongly predicts vulnerability to food insecurity.

Poverty itself is a somewhat contested term. Some understand it as being defined in absolute terms based on a single monetary dimension such as income level (heretofore referred to as the economic model of poverty). Others understand it as a relative phenomenon linked to the ability to achieve well-being and health, although an individual may or may not exercise that ability in action (Nussbaum 2011). This later view of poverty is known as the capabilities approach. According to Sen, who first developed the Capabilities approach, addressing poverty must consider people’s diverse needs and characteristics and their inability to achieve key ‘beings and doings’ that are basic to human life, such as feeding oneself and one’s family.

How poverty is conceptualised has implications for understanding its effects individually and cumulatively and addressing poverty and its impact. The economic model sees the effects of poverty as it relates to food security as the inability to afford food and measures it as going without. In this framing, the solution is to give people food or money to purchase food. Because it is multi-dimensional, the capabilities approach focuses on what people can or cannot do and gives room for understanding the implications of those constraints on the ability to do as the effects of poverty (Conconi and Viollaz 2018). Concerning food, this is calculated according to the ability to be food secure, which might include purchasing healthy food but also has other possibilities, such as the ability to grow, cook, or carry it home from where it is obtained. These different possibilities work together to determine the ability of someone not to be malnourished or hungry. This approach also gives room to understand how a person’s circumstances (e.g., being in good mental and physical health), their geographical contexts (local and national), and their orientations toward certain doings shape their capabilities. Addressing food security within this more complex and multi-dimensional understanding means enhancing people’s access to the necessary tools to avoid food insecurity.

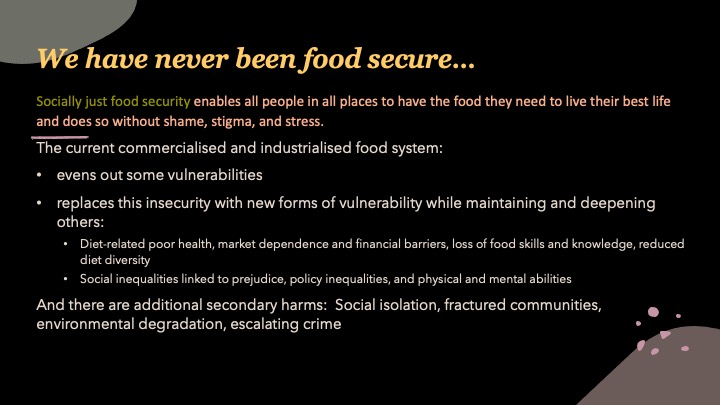

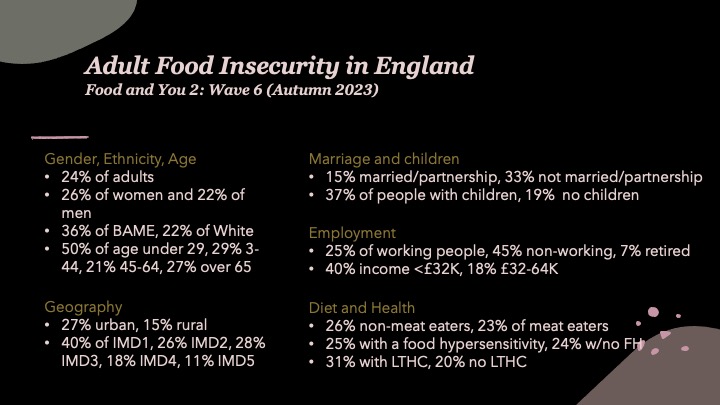

The United Nations Development Programme adopts the capabilities approach to addressing poverty, and capabilities directly inform how they conceptualise food security. How poverty and food security is predominantly understood and measured in economically developed nations follows the economic model. This is evidenced by the questions used in the USDA food security module that emphasise the affordability of food and do not consider other aspects that also influence the ability to be food secure. There is also a prevailing myth that countries commonly conceived of as economically developed (e.g., the United States and Canada, most European Countries, Australia, and New Zealand) are food secure. However, among these nations, there is significant variation. For example, in England, an economically wealthy nation, one in five adults was classified as having low or deficient food security (Armstrong et al., 2023). In Sweden, a country typically understood as having high levels of food security; evidence suggests food insecurity is still relatively low but increasing (Rost and Lundalv 2021). Given that there is food insecurity in wealthy countries, research and interventions need to be implemented in these countries and the countries that have traditionally been the focus.

FOOD POVERTY OR THE CAPABILITY TO BE FOOD SECURE

While we may intuitively understand poverty, it is often not a term people use to describe themselves. People can apply it to others whose life experience is worse than their own: That person living on the street, the child who comes to school in old clothes and is chronically hungry, the people living in a shelter rather than a home, someone somewhere else. This section outlines the economic model that casts food insecurity as food poverty and highlights some of the limitations of this approach. The section then turns to a discussion of the capability approach as applied to food security and sketches out the need for a systems perspective that considers the different forms of resources or tools needed to achieve food security beyond just the finances. The section argues that interventions must focus on multiple scales, not just individuals or households, to address food security.

Food Poverty

Food poverty is a sub-category within the economic understanding of poverty. In this approach, poverty is the lack of sufficient income necessary to purchase a bundle of goods to guarantee survival, and food poverty is the lack of income to buy enough food required. Rowntree (1902, 2000:133-4) defined poverty as mere physical existence in, what is arguably, the subject’s first scientific exploration. When income is inadequate to meet all needs, the only recourse is to cut back on food. This, he argues, sacrifices physical health because food intake is insufficient. Food poverty is frequently used by researchers, policymakers, the press, and charities in economically developed nations.

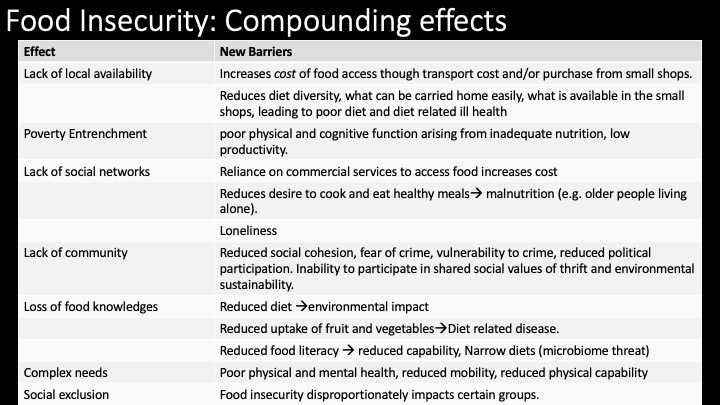

The economic model reduces food to calories, whereby food insecurity equates to insufficient calories to maintain energy (Burchi and De Muro, 2012). Rowntree’s study was undertaken in an era before highly processed foods, characterised by high calories and low nutrients, were available at prices often considerably lower than those that help maintain a healthy life. The transition to a food system that has introduced these high-calorie, low-nutrient foods means that the physical manifestation of undernourishment is no longer reducible to being underweight. The food-poverty nexus is manifested as an increased risk of diet-related health outcomes that disproportionately affects those who struggle financially. These health inequalities, in turn, deepen poverty. They do so by undermining the physical energy needed to maintain or improve one’s circumstances, extending the duration and magnitude of the harm caused by poor health and increasing the financial burden that living with poor health extracts (Dowler 1998).

Acknowledging the importance of sufficient nutrients as a critical aspect of the food-poverty nexus is an important area of investigation by nutrition, medicine, and public health scholars. However, it sits awkwardly in the economic model. This approach reduces food to a financial exchange. Focusing on the ability to make a transaction (e.g., buy food) in each moment does not consider the cumulative effects that transactions can have (e.g., purchase of low-nutrient food leading to poor health). When people purchase low-quality food, the public health response assumes they are making poor choices because they do not understand what healthy food is or its importance. However, within economic rationality, people purchase low-nutrient foods. They provide better value for money than high-nutrient foods because they are filling, taste good, and are less likely to be wasted (Blake 2019).

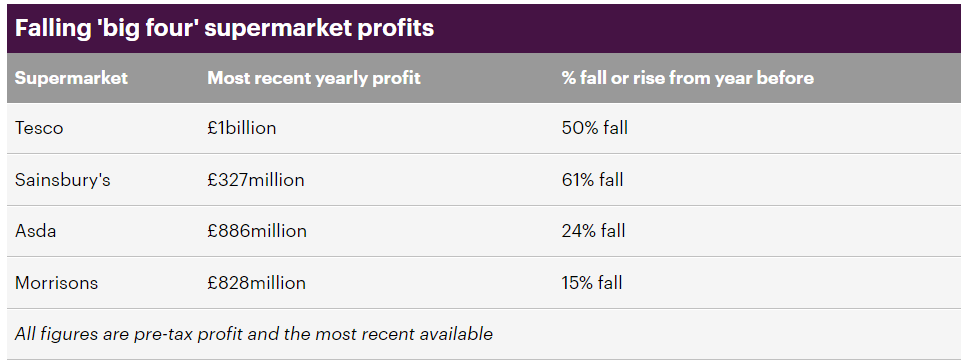

Another way that the economic model positions itself awkwardly is that it presumes that the economic market is the ideal location to source food. Not only does this approach discount the other ways that people access food, but it promotes a solution to engage with the same market that contrived a food system dominated by cheap, unhealthy food. Nothing in the economic model directly challenges the contributing role that market actors who commercially supply food play in producing poor nutritional outcomes and lack of food access for people in places with a concentration of poverty. Indeed, it is possible that providing a cash transfer so that people can purchase food may result in deepening health inequalities as there is little incentive to re-introduce healthy foods into these localities by these actors. There is little evidence that providing cash increases diet diversity.

Changing what people understand to be food, shifting diets, and increasing diet diversity is critical for addressing climate change and improving health. Because of its transactional focus, the economic model does not acknowledge the issues presented by entrenched food cultures among people experiencing poverty. In wealthy countries, where highly commercial food systems have long operated, these food cultures are characterised by narrow diets and low uptake of fruits and vegetables (Dowler and Turner 2001). Nor does it halt the transition from more traditional diets toward high environmental impact diets that are also highly processed and occurring in countries considered less economically developed, such as Uganda (Auma et al. 2019). These transitions are caused by introducing convenient, low-cost, shelf-stable, low-nutrient foods combined with a positive lifestyle narrative that makes these foods attractive.

Finally, the economic model takes the household and what happens with food within it as a black box. It assumes that food allocation within households is equal. However, evidence shows that parents feed children first, and mothers are likelier to skip meals to ensure other family members are fed (Dowler and Turner 2001). There is also no acknowledgement that other demands, values, and emotions may influence what and how much is eaten. For example, poor mental health makes planning difficult, poor physical health makes it difficult to stand at a cooker, addictions divert resources, or lack of motivation to cook because of living alone.

The Capability to be Food Secure

In Hunger and Public Action, Dreze and Sen (1989) set out the capabilities approach and its links to hunger when arguing a shift from instrumental control over commodities toward a focus on human capabilities. They argued that it is means rather than ends that are important as ends operate in the immediate, whereas means allow for addressing needs now and in the future. Thus, for them, “A more reasoned goal would be to make it possible to have the capability to avoid undernourishment and escape the deprivations associated with hunger (p.13)”. In doing so, the approach acknowledges all four pillars of food security identified by the UN.

The four food security pillars include access, availability, utilisation and stability. While a narrow conceptualisation of access as affordability is acknowledged in the economic model, the other aspects are not. In the capabilities framing, access also comprises other means, such as the absence of legal or religious barriers or the presence of social networks through which food is given. Availability is the presence of food in the place where people are. If there is no food close enough to where people are, it will not be available regardless of cost. Utilisation, a vital component of the capabilities approach, involves knowing how and being able to process, store and cook food safely. It also includes knowing if certain things are edible or will cause personal harm; for example, they will not be poisonous, cause an allergic reaction or induce an otherwise adverse reaction. Utilisation also includes access to complementary inputs, for example, cooking equipment, fuel or electricity, sanitation, and water. Stability means having all of these all of the time and is what offers security. This means having national and local-scale policies and infrastructures in place to ensure food is produced or imported to meet population needs and provide people with opportunities to acquire the resources needed to access food.

Resources in this context extend beyond money that can be exchanged for food to include other elements that enhance the capability of someone to be able to achieve food security. We can think of money as a communicative resource that enables smooth exchange between buyer and seller. Money in the household context must be exchanged for its use value to be realised and then replenished. Social capital, although potentially less efficient than money, is also a communicative resource that must be replenished if used. A second form of resource, assets, contribute their utility not by being exchanged but by being used. Assets are both intangible and tangible. Intangible assets include but are not limited to health, knowledge, motivation, inventiveness, and know-how. Tangible assets include things such as land or equipment, including cooking equipment. Selling one’s cooking utensils may enable food to be purchased now, but the problem of how to cook food today and tomorrow arises instead and undermines security. There are also place-based resources that enable food security and that support both communicative resources and assets. Local resources that enable the replenishment of communicative resources include a local labour market that provides good jobs that pay sufficient wages for the time spent working and is open to all. Linked to this is childcare that supports people to take advantage of that labour market while protecting their children. Community spaces and activities enable the development of social networks, as do opportunities to participate in social life. Those that enhance assets include, for example, a foodscape that provides the diversity of food needed to live a healthy life and does so without bias and few limitations, a health and welfare system that protects people when they need support, an education system that enhances people’s knowledge and know-how, and safe outdoor spaces that facilitate good health.

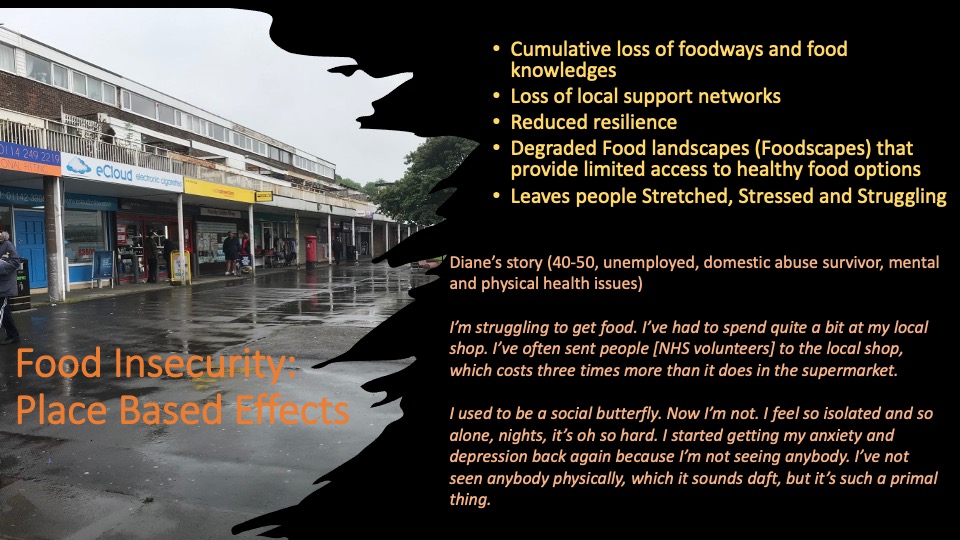

The UN argues that all four pillars must be present for food security to be achieved and maintained. Vulnerability to food insecurity arises when communicative resources are not replenished and assets and local resources are not maintained. Sen clearly states that different people have different abilities to be food secure based on their unique circumstances, the resources they control, and their contexts. Place plays a central role in the capability to be food secure. Physical, social, legal, political and economic processes determine what is in a place and how resources are available to people to access and utilise food to maintain health and well-being. Geographical concentrations of people with few resources lead to the creation of unhealthy or barren foodscapes. An inability to socialise, linked to the inability to share food, leads to isolation. This isolation, in turn, increases social divisions and fear of crime. At the same time, anti-social behaviour that arises from feelings of anger that result from hunger and disadvantage reinforces this fear, leading ultimately to community breakdown. Thus, to increase the capability to be food secure, we must develop both people and places so that they can act in ways that ensure their food security.

FOOD AND POVERTY FUTURES

As the previous section argued, food security capability is complex, and it is not sufficient to focus only on access to food in the immediate. Basic capabilities such as achieving or maintaining good health, being educated, and having the opportunity to participate in household decisions and community life are also needed (Burchi and De Muro 2012). In short, we must develop human capability, including in high-income nations. This suggests several future challenges and needs that shape how we understand and act on this relationship going forward.

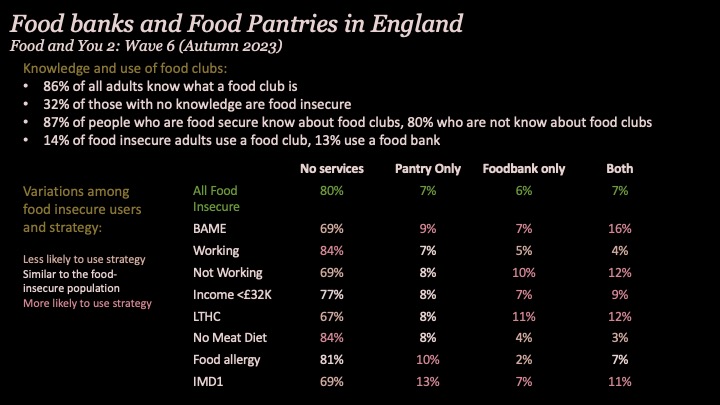

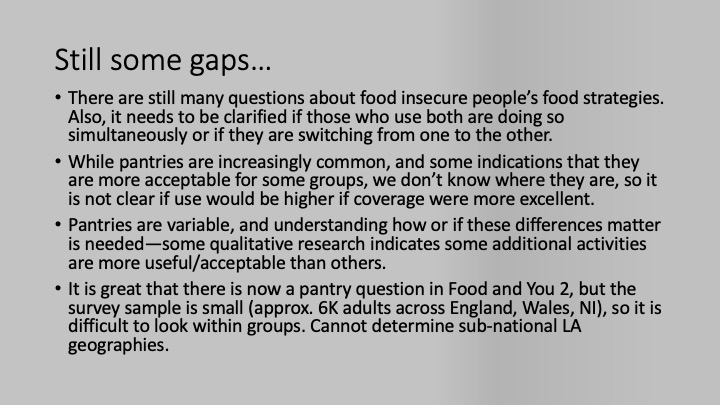

To know where to provide support, better data that captures these capabilities is needed. As mentioned above, many wealthy countries collect food security data based on affordability. While this data is only a partial picture of food security, it is made more partial by the lack of a fine enough geographical scale. Local-scale data linked to administrative units can use policy to target and repair the localities within which struggling people live, which is needed for intervention and decision-making.

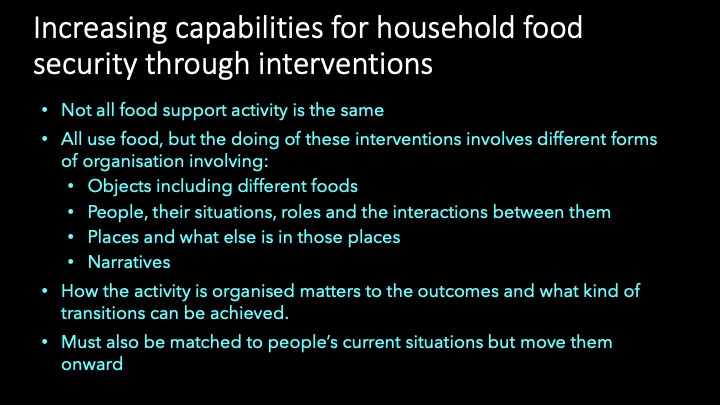

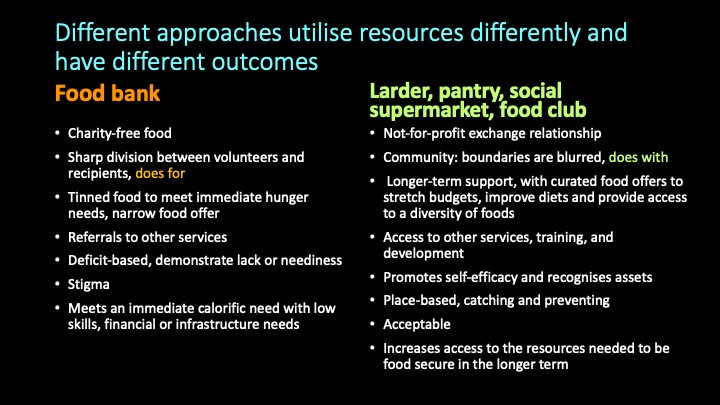

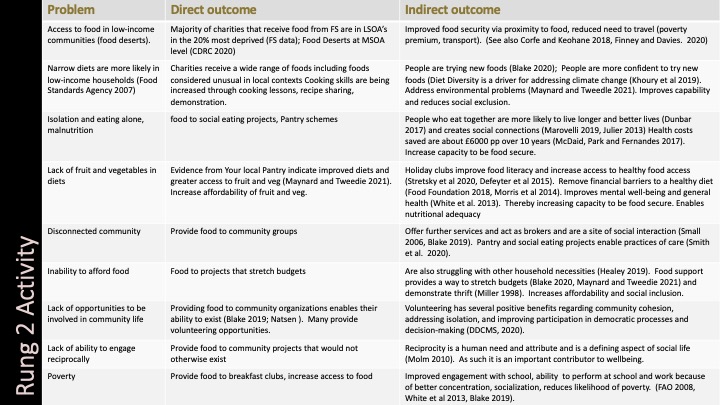

While we know that different approaches to addressing people’s food insecurity vary in their effects, for example, considerable stigma is associated with charity food parcels. People who use low-cost food clubs, food hubs, or so-called social supermarkets that are place-based report feeling more connected to their communities, increased diet diversity, and increased uptake of fruits and vegetables. Provider evaluations of voucher schemes for fruits and vegetables report dietary improvement and increased diversity. Children’s school meals and breakfast clubs are linked to children’s readiness and ability to learn. There is a need to understand what other interventions would support and be acceptable for people who struggle to achieve food security. There is also little systematic research examining how different interventions enhance access to the resources needed to achieve food security. There is a lack of research that systematically compares outcomes from other interventions. This research would support those seeking to improve population health and well-being and increase food security to make informed decisions regarding services to introduce and support.

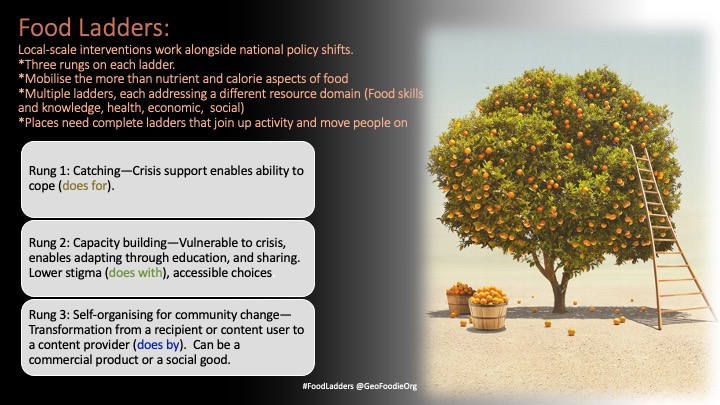

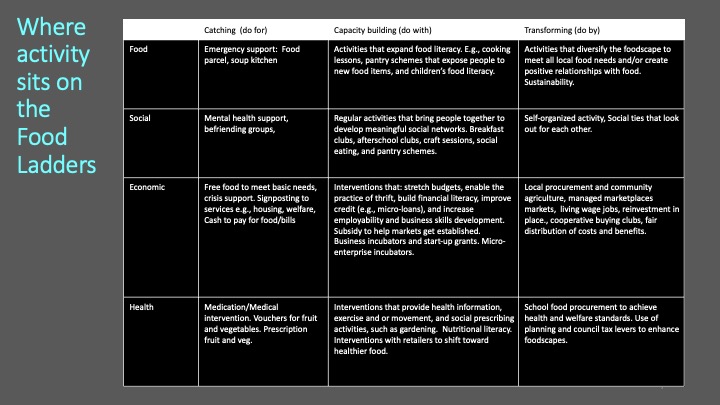

But there are hungry people now. It is also quite likely that there will be hungry people who need emergency support in the future, even if we build capabilities. To that end, I have created a framework for thinking not only about how to transition people away from charity emergency food support but to provide them with immediate help when they need it urgently. The Food Ladders framework positions emergency support as the bottom rung. This should be immediate and temporary. It can be in the form of cash or food, although quite often, by the time people reach urgent need, cash may not be the right answer to ensuring they are fed. The ladder’s second rung is where the focus of most effort and support should be. This is the capabilities rung. The activity enhances people’s assets so they can acquire the resources they need to achieve food security. The final rung is the transforming rung. These are the activities whereby our food system shifts from one that is harmful to one that nurtures people. It could include a more cooperative form of market. It may be more local. It focuses on food that meets nutritional needs, self-organised effort, social connections and local prosperity.

To meet the sustainable development goals, household capabilities and the contexts that help shape those capabilities must be addressed. A considerable body of research and innovation has focused on countries where food insecurity is recognised. Research and activity are also needed that consider how existing learning and innovation could be adapted for economically wealthy countries.

REFERENCES

Armstrong, B, King, L, Clifford, R, Jitlai, M, Jarchlo, AI, Meers, K, Parnell, C, and D Menasah 2023. Food and You 2—Wave 5. [Available Online https://www.food.gov.uk/research/food-and-you-2/food-and-you-2-wave-5] Food Standards Agency. (Date Accessed 12 July 2023)

Auma, C. Pradeilles, R, Blake, M, and M Holdsworth 2019. What can dietary patterns tell us about the nutrition transition and environmental sustainability of diets in Uganda, Nutrients 11(2):3422 https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11020342

Blake, M K (2019) More than Just Food: Food Insecurity and Resilient Place Making through Community Self-Organising, Sustainability 11, no. 10: 2942. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11102942

Burchi, F and P De Muro (2012) A Human Development and Capability Approach to Food Security: Conceptual Framework and Informational Basis. [Available Online: https://www.undp.org/sites/g/files/zskgke326/files/migration/africa/Capability-Approach-Food-Security.pdf], UNDP. (Date Accessed 14 June 2023).

Conconi, A, and Viollaz, M. (2018) Poverty, Inequality and Development: A discussion from the Capability Approach’s Framework, in BBVA OpenMind (eds) The age of Perplexity: Rethinking the world we knew. [Available Online https://www.bbvaopenmind.com/en/articles/poverty-inequality-and-development-a-discussion-from-the-capability-approach-s-framework/], Penguin House Grupo Editorial. (Date Accessed 14 June 2023).

Dreze, J and A Sen (1989) Hunger and Public Action, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Dowler, E (1998) Food poverty and food policy. IDS Bulletin, 29(1), pp.58–65.

Dowler, E, and S Turner (2001) Poverty Bites: Food Health and Poor Families. London: Child Poverty Action Group.

FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP and WHO (2022) The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2022 [Available Online https://www.fao.org/documents/card/en/c/cc0639en] Rome: FAO. (Date Accessed 12 July 2023).

Nussbaum, M. (2011) Creating Capabilities: The Human Development Approach. Cambridge and London: Harvard University Press.

Rost, S and J Lundalv, (2021) A systematic review of the literature regarding food insecurity in Sweden, Analysis of Social Issues and Public Policy, 201:1020-32. https://doi.org/10.1111/asap.12263

Rowntree, B S, (2000) Poverty A Study of Town Life, Centennial Edition (Reprinted edition), Bristol: Policy Press.

FURTHER RECOMMENDED READING

The following further reading elaborates and summarises the capabilities approach to poverty and food security and provides a valuable commentary on its implications and future directions.

Burchi, F and P De Muro (2012) A Human Development and Capability Approach to Food Security: Conceptual Framework and Informational Basis. [Available Online: https://www.undp.org/sites/g/files/zskgke326/files/migration/africa/Capability-Approach-Food-Security.pdf], UNDP. (Date Accessed 14 June 2023).

Conconi, A, and Viollaz, M. (2018) Poverty, Inequality and Development: A discussion from the Capability Approach’s Framework, in BBVA OpenMind (eds) The age of Perplexity: Rethinking the world we knew. [Available Online https://www.bbvaopenmind.com/en/articles/poverty-inequality-and-development-a-discussion-from-the-capability-approach-s-framework/], Penguin House Grupo Editorial. (Date Accessed 14 June 2023).

Hick, R (2011) The Capability Approach: Insights for a New Poverty Focus, Journal of Social Policy, 41(2): 291–308. doi:10.1017/S0047279411000845

You must be logged in to post a comment.